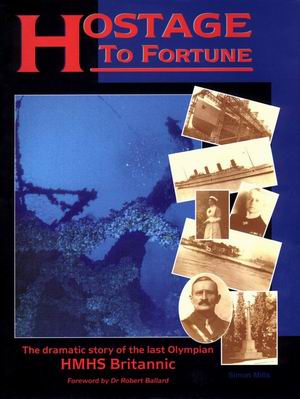

‘Hostage To Fortune: The Dramatic Story of the Last Olympian’

Author: Simon Mills

ISBN:1-899493-03-4 / Price (UK): £28.50

Hardback, 224 pages

Review by Mark Chirnside

Simon Mills’ latest book cannot be accused of being too short. There are more than two hundred pages filled with informative text and a variety of interesting, and rare, photographs and illustrations. What the author himself aimed for, as he said when he began work on compiling the book in the late summer of 1999, was a book that was ‘very different from "Last Titan". Indeed, it is, for the emphasis clearly seems to be on the human aspects of the disaster, as opposed to the technical focus – although there is something in the book that should please everyone.

One of the book’s finest features are the rigging plans of the Britannic, one showing her as she was intended to be outfitted as a passenger liner, and the other showing her actual arrangement as a Hospital Ship. The usual general arrangement plans make up the book’s front and rear endpapers, and the inclusion of these plans will be of great interest to technical students of the Britannic. Certainly the plans are of good quality, although unfortunately my own copy of the book came with these plans rather awkwardly creased and with the edges stuck together. This can hardly be blamed on the author or contributors, as it is a printing or binding error. Yet these are a wonderful resource for Britannic modelers.

Speaking as someone more interested in the technical aspects of Britannic, I was slightly disappointed that there was not more technical content, yet that is more than made up for by the extensive human content of the work – and the human aspects of the ship’s life were, after all, the work’s prime focus. Many Britannic students will have access to sources such as ‘Engineering,’ yet newer students interested in the technical side would do better to refer to ‘The Last Titan.’ However, it is apparent that some technical matters (including the general arrangement plans) have been included in the new book for those ‘techies’ such as myself.

While the book explains correctly and in some detail the concept of a ship’s metacentric height, crucial to stability and a vessel’s sea keeping qualities, there seems to be a minor mistake with regard to the ship’s width. The author has corrected the belief that Britannic’s double skin contributed to her additional width, for this is false – Britannic was intended to be wider before the 1912 redesign. Stating that according to 1912 specifications Britannic was intended to be 93 feet 6 inches wide, and that according to 1914 documents the vessel was 94 feet in width, the text asks where the extra six inches came from, and speculates that it was due to the lifeboat design changing after spring 1912. (Pages 17 – 20.) While it is undoubtedly correct that the addition of the larger and heavier lifeboats would have effected the ship’s metacentric height, Britannic’s width had already been confirmed as eighteen inches wider to Lord Pirrie in late 1911, for we must not forget her much more lavish accommodation which would have given her extra top weight – especially in first class, with the additional private baths, marble fittings and other features. It seems apparent that this extra width (confirmed in 1911) was enough to allow even the new gantry davits to be fitted when the design was changed after Titanic’s loss; and the six inch discrepancy can easily be explained, for it is the difference between an ‘Olympic’ class liner’s moulded and extreme breath. Although such details are debatable to an extent, there seems to be little or no supporting evidence in the book that six inches were added to Britannic’s width in 1912, especially since her construction was already well under way, and even slight changes to a vessel’s width or length necessitate enormous changes to the shaping of the hull frames, plates and girders – indeed, the entire structural design details.

Interestingly, the book states Britannic’s intended complement of lifeboats was forty-four in total – yet there are in fact a number of variations even within the source that the author used, and so it might have been an improvement if there had been some more text outlining the possible configurations. There are interesting possibilities, backed up by various sources, as to forty-six or forty-eight boats in total. It is only a very minor area of criticism, yet a more complete discussion of the lifeboat configuration would no doubt have been of use for modelers.

In the work there is an extensive use of accounts from those who sailed in Britannic, watched her, or survived her sinking. The book contains a great expansion on the U73’s story, including Martin Niemoller’s memories, and her crew prior to and following the sinking. And there are even interesting details as to the class of submarines she belonged to, including diagrams and other technical information that will be of interest to many readers – for the U73 can all too easily be overlooked in accounts of the Britannic’s sinking. Arguably, that is because the ‘mine verses torpedo’ debate has still not been definitively resolved. Aboard Britannic, the book details her sinking comprehensively working off a variety of important accounts from people who were there; many of these accounts have been under-utilised in the past, and to my knowledge the last time that some of these appeared was during the 1970s and early 1990s, in the THS’s venerable ‘Commutator.’ There are a few accounts that were not included in the book, but you cannot include everything in a single volume and this might be considered nitpicking.

It is also important to mention those details of Britannic as a Hospital Ship that have surfaced in this book. On pages 34 and 35, augmented by Percy Tyler’s account on page 87, appear details of the ship’s layout and her wards – details which prove some previous ‘knowledge’ inaccurate or misleading. It is unfortunate that no detailed plans of the Britannic’s layout seem to exist, for there are certainly plans in existence of the Olympic when she was outfitted as a troopship, showing her layout. If plans of Britannic’s interior as a hospital ship did exist, it would make life much easier for anyone wanting to do a ‘cutaway’ model of the ship in her HMHS configuration.

There is fascinating information on those people who survived the disaster, from Captain Bartlett to Sheila Macbeth and others. Even Martin Niemoller is included, a patriotic and decent man who fell out of favour with Hitler in the late 1930s. While Britannic’s Assistant Captain Harry William Dyke has long been a mystery in terms of his career details after the sinking, his name appears on Olympic’s crew manifest as early as the end of December 1916 – a detail which seems to have been overlooked in the book, which merely states that Guildhall Library files have nothing after 1916. (It seems unlikely to me that two men could have identical names, and work for the same company in the same positions.)

Perhaps the finest part of the book is that discussing the wreck; much new information came out of the 1997, 1998 and 1999 expeditions which was generally not well publicised – although the expedition teams have done excellent work in presenting their accounts through the internet. Britannic expeditions understandably do not attract the same attention as those to Titanic, save perhaps – in the maritime community – for the 1995 visit, and nor do their findings receive as much publicity. Simon Mills has been the owner of the wreck since 1996 and presumably has access to practically everything ever discovered at the site. Information in the chapter appears to include that from the 1998 research paper on Britannic, completed by an American Panel of marine forensic consultants. This is especially valuable since Britannic enthusiasts seem to be at a loss to obtain copies of this report, and indeed it seems to be a rare document, compared to the publicity Titanic reports have received. Combined with the online expedition records, this book will help form a valuable set of resources for anyone wanting to model the ship as she is today on the ocean floor.

I heartily recommend this work and we can only hope that Britannic gains the interest she deserves. While there might be some minor errors, there is certainly more than enough new and fascinating technical and human content to be of interest to any Britannic buff. At a stroke it is the most comprehensive single volume on Britannic’s history, and what you get is worth the money. From a modeller’s viewpoint, there is a great deal of useful information.

MC ~ 03/04